Pro wrestling is one of the most misunderstood forms of entertainment in modern history. Is it a sport? Is it drama? Is it fake? Is it real? The answer to all of those questions is yes… and no. But to really understand what pro wrestling is, you have to stop looking at it through the lens of traditional sports and start seeing it for what it’s always been: a business rooted in hustle, spectacle, and deception — a modern-day carney show wearing the mask of a competitive sport.

Let’s get into it.

At its core, pro wrestling is storytelling through physicality. The hits are very real. It’s choreographed combat basically designed to evoke emotion — whether that’s cheers for the hero, boos for the villain, or gasps when something unexpected happens. Unlike competitive sports where outcomes are determined by performance in clutch moments, professional wrestling matches are predetermined. That doesn’t mean they’re easy to do. That doesn’t mean they’re fake.

The bumps hurt. The injuries are real. The toll it takes on the human body — mentally and physically — is undeniable. Wrestlers don’t get offseasons. They’re athletes, directors and actors combined, expected to perform through pain and keep the audience emotionally invested night after night.

So when someone yells, “Pro wrestling is fake!” — they’re missing the point entirely. In boxing, MMA, football, and baseball, you’re watching athletes compete within a set of rules to win. The outcome is uncertain. The drama is unscripted.

In wrestling, the outcome is known ahead of time — but the goal isn’t just to win. It’s to make the audience feel something. To take them on an emotional ride. The goal is to draw money by telling compelling stories. Think of it like this: if boxing is a competitive sport, then pro wrestling is a simulated fight for money, like stunt work crossed with soap opera drama. It’s Broadway with body slams.

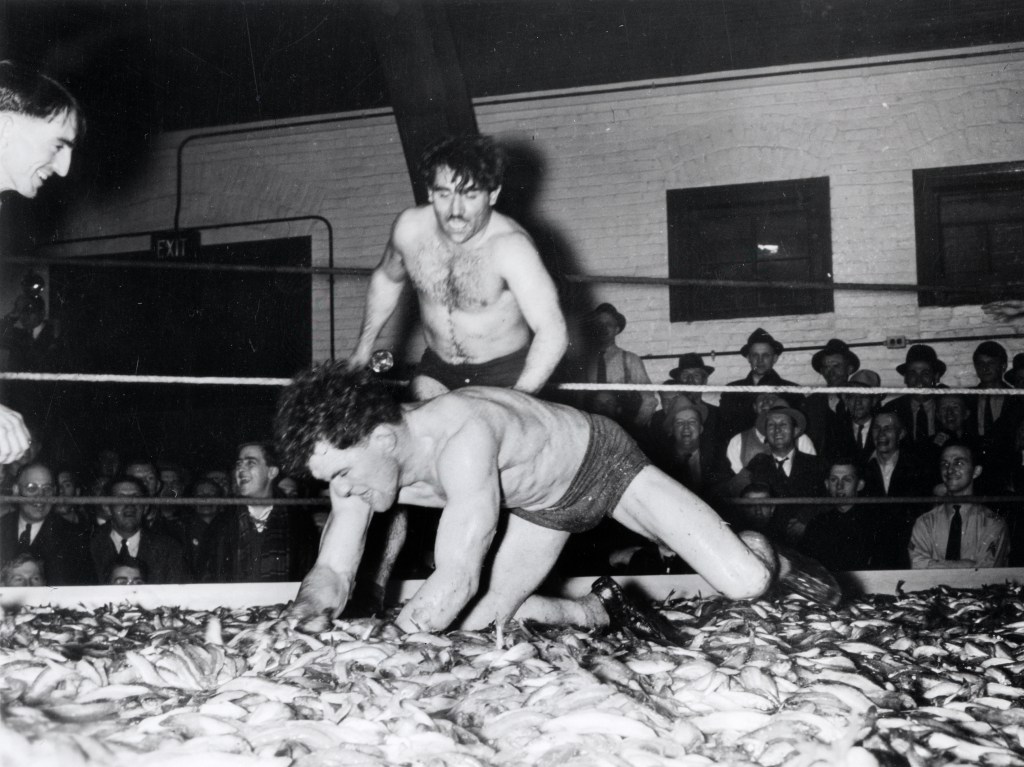

To really understand the nature of the wrestling business, you have to go back to its roots — the carnival. In the early 20th century, wrestling was part of traveling carnivals and sideshows. There were legitimate “shooters” (tough guys trained in catch wrestling or submission grappling) who would take on locals in “open challenges”. These contests were sometimes legit… and sometimes weren’t. Sometimes the match was fixed. Sometimes the outcome was agreed upon beforehand. Sometimes the local challenger was a plant. Someone in on the work.

This is where the term kayfabe comes from — a carney slang word for “keep it fake”. You never broke character. You never let the audience know it was a work. The illusion was sacred, because protecting the con was protecting the business was protecting your livelihood. Wrestling was a con. It was a hustle. It was about getting people to pay money to see a fight they believed was real, even if it wasn’t.

As wrestling evolved out of the carnival circuit, it kept those carney principles. Legitimate grappling — known as catch wrestling — was blended with prearranged finishes. Promoters realized they could protect their stars from injury and extend rivalries for months or even years by working the matches instead of fighting them for real.

These promoters and wrestlers eventually formed loose alliances, often sharing talent and protecting each other’s business by not running shows in each other’s towns without permission. This laid the foundation for what became known as the territory system.

From roughly the 1940s through the early 1980s, the United States (and parts of Canada) were divided into regional territories, most under the umbrella of the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA). Each territory had its own promoter, its own local television program, and its own local stars.

Some territories became legendary:

Mid-South Wrestling (promoter Bill Watts) with its hard-hitting, athletic style.

Jim Crockett Promotions in the Carolinas, which showcased Ric Flair, Dusty Rhodes, and the Four Horsemen.

AWA in Minnesota with Verne Gagne’s technical focus.

Memphis Wrestling with Jerry Lawler’s over-the-top feuds and wild brawls.

World Class Championship Wrestling in Texas with the Von Erichs and the Freebirds.

Los Angeles had it’s territory running out of the Grand Olympic Auditorium.

The NWA World Champion — often a legitimate tough guy — would travel from territory to territory defending the Worlds championship. His job wasn’t just to put on great matches; it was to make the local babyface look like a hero before eventually beating him, protecting the champion’s credibility while elevating the hometown star.

In the territory days, kayfabe was life. Heels and babyfaces never traveled together. You didn’t break character in public. The audience believed and the promoters made sure that illusion stayed intact. The system worked because wrestling was localized. Fans were loyal to their territory, their stars, and their TV program. But that loyalty also made the business vulnerable to someone with a bigger vision.

Enter Vince McMahon and his National Expansion. In the 1980s, everything changed. Vince McMahon Jr., the son of an NWA promoter, had a different vision. He saw wrestling not as a regional hustle, but as a global entertainment product. He bought out his father’s promotion (the WWF) and began signing top talent from other territories. Hulk Hogan. Roddy Piper. Randy Savage. Junkyard Dog. Harley Race. He used cable television deals and marketing to nationalize the product, taking control the media, expanding WWF’s reach far beyond what anyone thought possible.

Wrestling exploded into pop culture. Wrestlers became action figures, Saturday morning cartoons, movie stars. And with this success came a shift: the old code of kayfabe began to crack. Vince even admitted during legal proceedings in the early ‘90s that wrestling was not a legitimate athletic competition, but “sports entertainment”. He was trying to avoid athletic commission fees and oversight. Some saw it as a betrayal of the business. Others saw it as the evolution of the hustle.

The Monday Night Wars was Real Business, Real Hustle. In the 1990s, the business exploded again — this time with WCW vs. WWF in the infamous Monday Night Wars. It was a war of ratings, money, and talent.

But it was also a war of believability. Fans were becoming more “smart” to the business. The internet was lifting the curtain. So the best promoters and bookers leaned into it — they blurred the lines between reality and fiction. Worked shoots. Real-life heat turned into storylines. Reality infused the product in a way that made you question what was legit and what wasn’t. In many ways, this was the peak of the carney hustle. Because even when you knew it was fake- you didn’t and it felt real again. That’s the magic.

Today, pro wrestling is part of a much larger media landscape. WWE is a publicly traded company, now owned by TKO Group Holdings, the same parent company as the UFC. AEW has emerged as a legitimate alternative, funded by a billionaire. There’s more access to wrestling than ever before, and more fans who know it’s a work. And yet — the hustle never died. Because the essence of pro wrestling remains the same: Tell a story. Protect the illusion. Get the audience to invest- even with modern tools like social media.

It doesn’t matter if fans know it’s predetermined. It matters whether they feel something when the match ends. Jim Cornette and others like him — who came up during the territory days — constantly stress the importance of kayfabe, believability, and protecting the illusion. Not because they’re stuck in the past, but because they know how fragile the hustle really is. They know how to draw money.

When you break kayfabe too much, when everything feels like a wink and a nod to the audience, when matches look fake or overly choreographed — the magic dies. The audience stops believing, even emotionally. Cornette’s rants aren’t just about being old school. They’re about preserving the most important part of the business: making people believe, even when they know better.

Wrestling Is Real and It’s the Realest Work There Is. Wrestling is real. It’s real in the bumps, in the broken bones, in the hours on the road, in the sacrifices made for a shot at stardom. It’s real in the backstage politics, the locker room egos, the contract disputes. It’s real in the hustle — in the grind of doing whatever it takes to get over and stay relevant. But it’s also a work. It’s a con. It’s a dance between performer and audience where both sides agree to suspend disbelief. That’s what makes it beautiful.

To understand pro wrestling is to understand that it’s never been just about matches. It’s about making people believe. It’s about taking something fake and making it feel more real than anything on TV. That’s why it survives. That’s why it thrives. That’s why professional wrestling is magical.

Leave a comment